President Muhammadu Buhari’s plan to lift Nigeria’s economy from its worst slump in a quarter century may entail short-term pain for potential long-term gain.

The blueprint released this month proposes ways to expand the economy by 7 percent by 2020 after a 1.5 percent contraction in 2016, the first full-year decline since 1991. It aims to create 15 million jobs by increasing oil output in the continent’s second-biggest exporter of the fuel, opening up farmland and boosting investment in power, roads and ports.

It also proposes to “allow markets to function,” with a market-determined exchange rate and cost-reflective power tariffs. This may see the currency weaken and electricity prices rise, which will hurt citizens, more than half of whom live on $1.90 or less daily, World Bank data show.

“We are about two years from an election, and as we get closer, the politics will become even more important,” said Michael Famoroti, an economist at Lagos-based Vetiva Capital Management. “We hope that populism won’t completely overshadow the economics of the plan.”

These charts explain why Buhari, whose term ends in 2019, may have to trade some political capital and risk possible social unrest if he implements the proposal as it stands.

While power prices are low relative to the continent, household utility costs in Nigeria are surging. About 2,500 megawatts of capacity is used for about 180 million people, who frequently endure supply cuts and resort to off-grid generators. South Africa, with a third of the population, produces at least 11 times more.

Buhari wants to introduce cost-reflective tariffs to attract power investment. When the government tried to raise prices 45 percent last year, labor unions took it to court and the plan was frozen. In 2016, distributors paid only 27 percent owed to generators, who in turn couldn’t fully pay for the gas needed to run their turbines.

“Power must be fixed, because it’s at the heart of the cost of doing business,” Famoroti said.

The central bank has kept the naira at about 315 to the dollar by selling the greenback and blocking access to the foreign-currency market for importers of items it deems non-essential. That’s forced some importers to buy dollars in the black market at about 30 percent more than the official rate.

Allowing market-determined rates will add to inflationary pressures for a country that’s a net importer of everything from refined fuel to food. Inflation slowed for the first time in more than a year in February to 17.8 percent, the statistics bureau said Tuesday, but is still above the government’s target of 6 percent to 9 percent.

“For a government that has previously described currency liberalization as a scheme to kill the naira, this is a huge step forward,” said John Ashbourne, an economist at London-based Capital Economics Ltd.

Adopting a more flexible exchange rate is irreconcilable with reducing inflation, which is close to the highest in more than a decade, and trimming interest rates, said Cobus de Hart, an analyst at Paarl, Cape Town-based NKC African Economics.

“If Abuja is aiming to achieve these goals simultaneously, it would suggest that the Central Bank of Nigeria’s strategy to move to a more flexible exchange rate will be a gradual one,” he said.

While debt as a percentage of gross domestic product at 13.5 percent last year was well below a global average of 56 percent, it has steadily increased and is set to peak at 16.1 percent in 2019, the Debt Management Office said.

The cost of servicing this debt was 50.3 percent of revenue last year and will remain above 40 percent through 2020, showing it “still remains highly vulnerable to persistent shocks in revenue,” the DMO said.

An improvement in debt-service costs is “unlikely, given the government’s track record of optimistic revenue assumptions,” said Gloria Fadipe, head of research at Lagos-based CSL Stockbrokers Ltd.. While output of oil — the government’s biggest income source — may improve, it’s doubtful that the production target of 2.2 million barrels daily that the 2017 revenue assumptions are based upon will be achieved, Fadipe said.

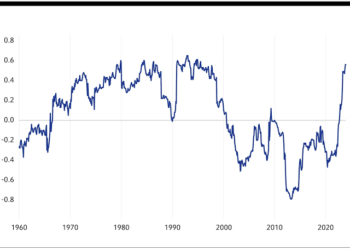

Vice President Yemi Osinbajo has led a peace initiative in the oil-rich Niger delta, asking militants not to renew bombing of pipelines, which cut output to almost three-decade lows in the third quarter, and hurt earnings from crude already reeling from low prices. With this and other measures including a new licensing round, Buhari’s administration targets an increase in production to 2.5 million barrels daily by 2020.

Achieving output goals will require “politically controversial negotiations” with militants, but should be technically possible, Capital Economics’ Ashbourne said.