Government’s fiscal deficit as well as rising inflation, among other reasons are said to responsible for high interest rate, according to some analysts.

Government’s fiscal deficit as well as rising inflation, among other reasons are said to responsible for high interest rate, according to some analysts.Consequently, as government year on year strives to close the budget deficit through sale of risk free instruments at higher rates, it inadvertently pushes cost of borrowing by the private sector with the attendant rise in interest rate to customers, they further argue.

Also, the Monetary Policy Rate, (MPR), anchor rate at which Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) borrows banks, currently at 14 percent is not helping matters as it pushes rates to customers at between 27 and 30 percent, when other overhead expenditures are considered.

“The government is competing with manufacturers, retailers, farmers and other ordinary business for funds. In some cases, it is offering 21 per cent returns on its risk free debt instruments,” Ahmed Ali the managing director of Mayor Farms, told MetroBusinessnews in an exclusive chat recently.

“With such high rates, what is the incentive for banks to lend to small businesses which come with risks,” he asks.

Indeed, CBN’s MPR currently stands at 14 per cent while commercial borrowers have to pay as much as 27 per cent interest on loans and in some cases almost 30 per cent on mortgage loans with maturities of less than three years.

But the rate at which government borrows is just a part of the problem, says Bongo Adi, an Economics Professor at the Pan African University, who identifies high inflation as one of the reasons why banks have to give loans at very high rates.

“Rise in inflation, occasioned by high cost of production has contributed to higher interest rates as well, says Adi. There is a positive correlation between interest rate and inflation, as inflation rises, interest rates must also rise. In the first nine months of 2016, inflation rose from 9.62 per cent in January to 17.85 per cent in September.

According to Adi, there is no way interest rate can reduce when you have an environment where inflation is rising and government is borrowing at a high premium.

Nigeria’s high interest rate situation contrasts sharply with rates in other countries. Average lending rate in the OCED hovers between 1-5 per cent even for long term facilities. In the United States, rates were as low as 1.63 per cent in September. Short term lending rate was much less.

In the days preceding the last Central Bank Monetary Policy Committee meeting, Nigeria’s minister of finance, Kemi Adeosun, called on the apex bank to cut rates so as to boost lending to the real sector.

“I don’t see interest rates reducing any time soon,” says Buchi Ejiogwu, head of Research and Strategic planning at Equator Capital, an Investment Bank in Lagos.

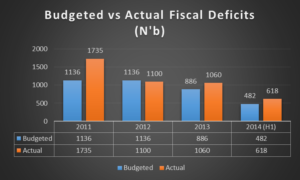

“The government has made its debt more attractive because it has to meet its budget obligations. The government is faced with a high deficit than expected because of the activities of militants in the Niger Delta region.”

Though the government has said that it is focusing on external borrowing with low interest rates, it nonetheless has played significantly in the domestic debt market thus competing in a market which is traditionally the major source of finance for small businesses.

“What makes it particularly bad for the agric sector is that when banks price loans, even for the agric sector, there is no deliberate effort at factoring in the sensitivity of the particular agric segment receiving the loans,” says Ali. “What we see is that banks give loans with exactly the same structure to say, a poultry farmer and a crop growers. That does not work anywhere.”

Any attempt to reduce the cost of borrowing must begin with taking away the incentives that make lending to the government much more preferred says Adi.